Temporomandibular joint

| Temporomandibular joint (Otolaryngology,Plastic Surgery, Dentistry ) | |

|---|---|

|

|

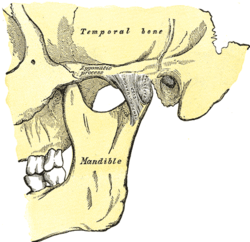

| Articulation of the mandible. Lateral aspect. | |

|

|

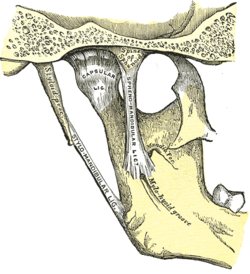

| Articulation of the mandible. Medial aspect. | |

| Latin | articulatio temporomandibularis |

| Gray's | subject #75 |

| Artery | superficial temporal artery |

| Nerve | auriculotemporal nerve, masseteric nerve |

| MeSH | Temporomandibular+Joint |

.jpg)

The temporomandibular joint is the joint of the jaw and is frequently referred to as TMJ. There are two TMJs, one on either side, working in unison. The name is derived from the two bones which form the joint: the upper temporal bone which is part of the cranium (skull), and the lower jaw bone called the mandible. The unique feature of the TMJs is the articular disc. The disc is composed of fibrocartilagenous tissue (like the firm and flexible elastic cartilage of the ear) which is positioned between the two bones that form the joint. The TMJs are one of the only synovial joints in the human body with an articular disc, another being the sternoclavicular joint. The disc divides each joint into two. The lower joint compartment formed by the mandible and the articular disc is involved in rotational movement-this is the initial movement of the jaw when the mouth opens. The upper joint compartment formed by the articular disk and the temporal bone is involved in translational movements-this is the secondary gliding motion of the jaw as it is opened widely. The part of the mandible which mates to the under-surface of the disc is the condyle and the part of the temporal bone which mates to the upper surface of the disk is the glenoid (or mandibular) fossa.

Pain or dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint is commonly referred to as "TMJ", when in fact, TMJ is really the name of the joint, and Temporomandibular joint disorder (or dysfunction) is abbreviated TMD. This term is used to refer to a group of problems involving the TMJs and the muscles, tendons, ligaments, blood vessels, and other tissues associated with them. Some practitioners might include the neck, the back and even the whole body in describing problems with the TMJs.

Contents |

Development

Formation of the TMJ occurs at around 12 weeks in utero when the joint spaces and the articular disc develop.[1]

Articulation

The TMJ is a ginglymoarthrodial joint, referring to its dual compartment structure and function (ginglymo- and arthrodial).

The condyle articulates with the temporal bone in the mandibular fossa. The mandibular fossa is a concave depression in the squamous portion of the temporal bone.

These two bones are actually separated by an articular disc, which divides the TMJ into two distinct compartments. The inferior compartment allows for rotation of the condylar head around an instantaneous axis of rotation,[2] corresponding to the first 20 mm or so of the opening of the mouth. After the mouth is open to this extent, the mouth can no longer open without the superior compartment of the TMJ becoming active.

At this point, if the mouth continues to open, not only is the condylar head rotating within the lower compartment of the TMJ, but the entire apparatus (condylar head and articular disc) translates. Although this had traditionally been explained as a forward and downward sliding motion, on the anterior concave surface of the glenoid fossa and the posterior convex surface of the articular eminence, this translation actually amounts to a rotation around another axis. This effectively produces an evolute which can be termed the resultant axis of mandibular rotation, which lies in the vicinity of the mandibular foramen, allowing for a low-tension environment for the vasculature and innervation of the mandible.[2]

The necessity of translation to produce further opening past that which can be accomplished with sole rotation of the condyle can be demonstrated by placing a resistant fist against the chin and trying to open the mouth more than 20 or so mm.

Components

There are six main components of the TMJ.

- Mandibular condyles

- Articular surface of the temporal bone

- Capsule

- Articular disc

- Ligaments

- Lateral pterygoid

Capsule and articular disc

The capsule is a fibrous membrane that surrounds the joint and incorporates the articular eminence. It attaches to the articular eminence, the articular disc and the neck of the mandibular condyle.

The articular disc is a fibrous extension of the capsule in between the two bones of the joint. The disc functions as articular surfaces against both the temporal bone and the condyles and divides the joint into two sections, as described in more detail below. It is biconcave in structure and attaches to the condyle medially and laterally. The anterior portion of the disc splits in the vertical dimension, coincident with the insertion of the superior head of the lateral pterygoid. The posterior portion also splits in the vertical dimension, and the area between the split continues posteriorly and is referred to as the retrodiscal tissue. Unlike the disc itself, this piece of connective tissue is vascular and innervated, and in some cases of anterior disc displacement, the pain felt during movement of the mandible is due to the condyle compressing this area against the articular surface of the temporal bone.

Ligaments

There are three ligaments associated with the TMJ: one major and two minor ligaments.

- The major ligament, the temporomandibular ligament, is actually the thickened lateral portion of the capsule, and it has two parts: an outer oblique portion (OOP) and an inner horizontal portion (IHP).

- The minor ligaments, the stylomandibular and sphenomandibular ligaments are accessory and are not directly attached to any part of the joint.

- The stylomandibular ligament separates the infratemporal region (anterior) from the parotid region (posterior), and runs from the styloid process to the angle of the mandible.

- The sphenomandibular ligament runs from the spine of the sphenoid bone to the lingula of mandible.

These ligaments are important in that they define the border movements, or in other words, the farthest extents of movements, of the mandible. Movements of the mandible made past the extents functionally allowed by the muscular attachments will result in painful stimuli, and thus, movements past these more limited borders are rarely achieved in normal function.

Other ligaments, called "oto-mandibular ligaments" [3][4][5], connect middle ear (malleus) with temporomandibular joint:

- discomallear (or disco-malleolar) ligament,

- malleomandibular (or malleolar-mandibular) ligament.

Innervation and vascularization

Sensory innervation of the temporomandibular joint is derived from the auriculotemporal and masseteric branches of V3 (otherwise known as the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve). These are only sensory innervation. Recall that motor is to the muscles.

Its arterial blood supply is provided by branches of the external carotid artery, predominately the superficial temporal branch. Other branches of the external carotid artery namely: the deep auricular artery, anterior tympanic artery, ascending pharyngeal artery, and maxillary artery- may also contribute to the arterial blood supply of the joint.

The specific mechanics of proprioception in the temporomandibular joint involve four receptors. Ruffini endings function as static mechanoreceptors which position the mandible. Pacinian corpuscles are dynamic mechanoreceptors which accelerate movement during reflexes. Golgi tendon organs function as static mechanoreceptors for protection of ligaments around the temporomandibular joint. Free nerve endings are the pain receptors for protection of the temporomandibular joint itself.

In order to work properly, there is neither innervation nor vascularization within the central portion of the articular disc. Had there been any nerve fibers or blood vessels, people would bleed whenever they moved their jaws; however, movement itself would be too painful.

Jaw movements

During jaw movements, only the mandible moves.

Normal movements of the mandible during function, such as mastication, or chewing, are known as excursions. There are two lateral excursions (left and right) and the forward excursion, known as protrusion. The reversal of protrusion is retrusion.

When the mandible is moved into protrusion, the mandibular incisors, or front teeth of the mandible, are moved so that they first come edge to edge with the maxillary (upper) incisors and then surpass them, producing a temporary underbite. This is accomplished by translation of the condyle down the articular eminence (in the upper portion of the TMJ) without any more than the slightest amount of rotation taking place (in the lower portion of the TMJ), other than that necessary to allow the mandibular incisors to come in front of the maxillary incisors without running into them. (This is all assuming an ideal Class I or Class II occlusion, which is not entirely important to the lay reader.)

During chewing, the mandible moves in a specific manner as delineated by the two TMJs. The side of the mandible that moves laterally is referred to as either the working or rotating side, while the other side is referred to as either the balancing or orbiting side. The latter terms, although a bit outdated, are actually more precise, as they define the sides by the movements of the respective condyles.

When the mandible is moved into a lateral excursion, the working side condyle (the condyle on the side of the mandible that moves outwards) only performs rotation (in the horizontal plane), while the balancing side condyle performs translation. During actual functional chewing, when the teeth are not only moved side to side, but also up and down when biting of the teeth is incorporated as well, rotation (in a vertical plane) also plays a part in both condyles.

The mandible is moved primary by the four muscles of mastication: the masseter, medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid and the temporalis. These four muscles, all innervated by V3, or the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, work in different groups to move the mandible in different directions. Contraction of the lateral pterygoid acts to pull the disc and condyle forward within the glenoid fossa and down the articular eminence; thus, action of this muscle serves to open the mouth. The other three muscles close the mouth; the masseter and the medial pterygoid by pulling up the angle of the mandible and the temporalis by pulling up on the coronoid process.

Disorders

- See Temporomandibular joint disorder for more details

The most common disorder of the TMJ is disc displacement. In essence, this is when the articular disc, attached anteriorly to the superior head of the lateral pteygoid muscle and posteriorly to the retrodiscal tissue, moves out from between the condyle and the fossa, so that the mandible and temporal bone contact is made on something other than the articular disc. This, as explained above, is usually very painful, because unlike these adjacent tissues, the central portion of the disc contains no sensory innervation.

In most instances of disorder, the disc is displaced anteriorly upon translation, or the anterior and inferior sliding motion of the condyle forward within the fossa and down the articular eminence. On opening, a "pop" or "click" can sometimes be heard and usually felt also, indicating the condyle is moving back onto the disk, known as "reducing the joint" (disc displacement with reduction). Upon closing, the condyle will slide off the back of the disc, hence another "click" or "pop" at which point the condyle is posterior to the disc. Upon clenching, the condyle compresses the bilaminar area, and the nerves, arteries and veins against the temporal fossa, causing pain and inflammation.

In disc displacement without reduction the disc stays anterior to the condylar head upon opening. Mouth opening is limited and there is no "pop" or "click" sound on opening.

TMJ pain is generally due to one of four reasons.

- The most common cause of TMJ pain is myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome, primarily involving the muscles of mastication.

- Internal derangements is defined as an abnormal relationship of the disc to any of the other components of the TMJ. Disc displacement is an example of internal derangement.

- Degenerative joint disease, otherwise known as osteoarthritis is the organic degeneration of the articular surfaces within the TMJ.

- TMJ pain remains one of the most reliable diagnostic criteria for temporal arteritis.

References

- ↑ Salentijn, L. Biology of Mineralized Tissues: Prenatal Skull Development, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine post-graduate dental lecture series, 2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Moss, ML. The non-existent hinge axis, Am. Inst, Oral Biol. 1972, 59-66

- ↑ Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, et al. (1998). "Anatomical considerations on the discomalleolar ligament". J Anat. 192 (Pt 4): 617–621. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1467815&blobtype=pdf.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, et al. (1993). "Relationships between the temporomandibular joint and the middle ear in human fetuses.". J Dent Res. 72 (1): 62–66. http://jdr.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/72/1/62.pdf.

- ↑ T Rowicki, J Zakrzewska. (2006). "A study of the discomalleolar ligament in the adult human.". Folia Morphol. (Warsz). 65 (2): 121–125. http://www.fm.viamedica.pl/darmowy_pdf.phtml?indeks=36&indeks_art=622.

External links

- Pain Resource Center, Inc. provides information on temporomandibular disorders and an on-line, widely researched, published and utilized screening and assessment test for both clinicians and patients to detect and measure the severity of temporomandibular disorders.

- Temporomandibular Joint Disorders (TMJD). Causes - Symptoms - Diagnosis & Treatment

- The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) - The Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health

|

|||||||||||||||||